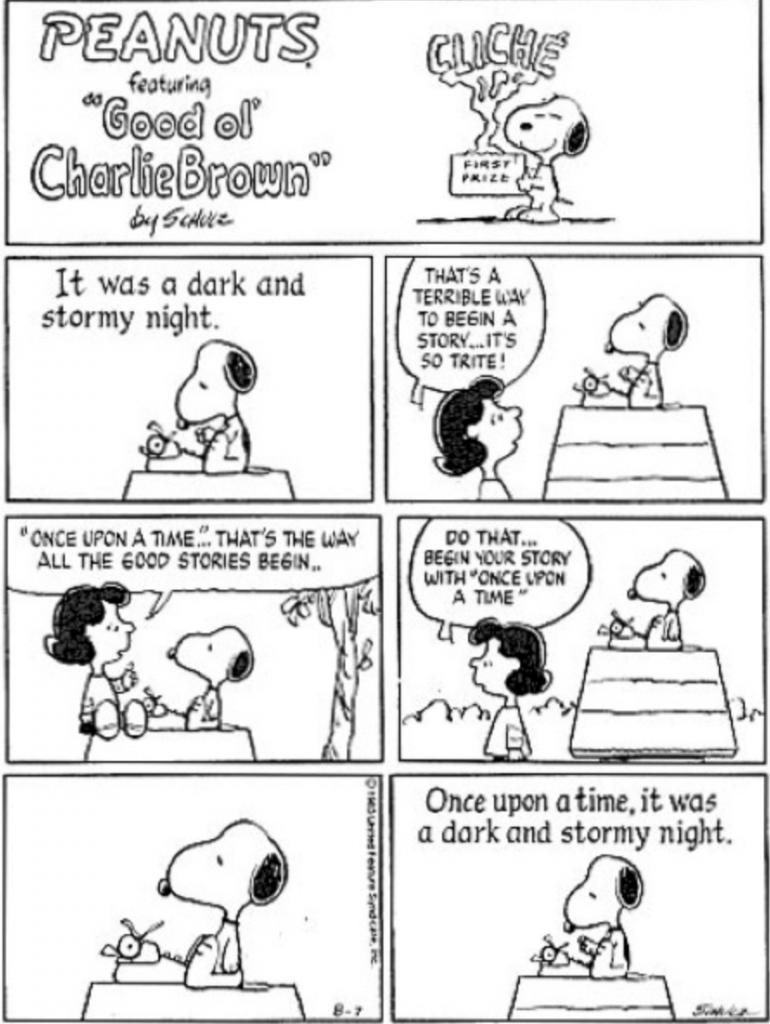

It’s cliché to begin a novel with the phrase “It was a dark and stormy night.” Snoopy immortalized the moody opener by using it to start all his novels in the Peanuts comics.

The phrase appeared in Sir Edward George Bulwer-Lytton’s 1830 tome Paul Clifford:

“It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents — except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets…”

Edward George Bulwer-Lytton

I won’t burden you with the rest of the paragraph! Basically, this opening is so over-described that it’s actually hard to picture.

It’s a perfect example of how not to start your novel. So much so that a university in southern California sponsors a Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest, where contestants compete to write the wordiest, most terrible novel opening ever.

If you’re working on your own novel, you could submit to the contest. Or you could focus on writing the best novel opening ever instead!

How to begin a novel: The importance of the first few paragraphs

When someone flips through a novel at the bookstore or library, they tend to read the first few sentences. Much of the time, a book goes back on the shelf because the first sentence or paragraph isn’t compelling to the potential reader.

But sometimes a book comes along that the reader doesn’t stop devouring until the librarian or bookstore clerk comes by and taps her on the shoulder, signaling closing time.

On Amazon, there’s a feature called “Look Inside,” which allows you to read the first few pages of a book before purchasing. Look Inside provides the same type of experience. Millions of potential buyers check those sneak-peek pages to make sure the book they’re buying is one they’ll actually read.

Authors sweat and fret over their first lines because of all of this. They’ve also given the world tons of fantastic examples of how to begin a novel. Here are a few favorite first phrases.

How to begin a novel: 5 noteworthy examples

From The Dry by Jane Harper

“It wasn’t as though the farm hadn’t seen death before, and the blowflies didn’t discriminate. To them there was little difference between a carcass and a corpse.”

Okay, Jane. I’ll keep reading!

From Winter Sisters by Robin Oliveira

“Two days before Emma and Claire O’Donnell disappeared, a light snow fell from the dawn sky above Albany, New York, almost as a warning mist.”

Who wouldn’t keep reading to find out what happened to the sisters? And don’t you love how Oliveira uses the setting to add to the tension in this line?

From There There by Tommy Orange

“There was an Indian head, the head of an Indian, the drawing of the head of a headdressed, long haired Indian depicted, drawn by an unknown artist in 1939, broadcast until the late 1970s to American TVs everywhere after all the shows ran out….If you left the TV on, you’d hear a tone at 440 hertz—the tone used to tune instruments—and you’d see that Indian, surrounded by circles that looked like sights through rifle scopes.”

Tommy Orange, a novelist and enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, starts his book bluntly. You can’t help but wonder where this horrifying anecdote is going, and what it’s going to mean for the rest of the novel.

From Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng

“Lydia is dead. But they don’t know this yet. 1977, May 3, six thirty in the morning, no one knows anything but this innocuous fact: Lydia is late for breakfast.”

Chilling, not only because of the staccato first line, but also because of the anticipation of the family’s horror upon finding Lydia dead somewhere.

From The Restaurant at the End of the Universe by Douglas Adams

“In the beginning, the universe was created. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move.”

Um…what? This line probably incites a smile, if not an outright chuckle. It proves that funny openings can be just as gripping as somber ones.

How to begin a novel: 5 tips for creating the perfect hook

The first line of a novel is called a hook because that’s what it should do: hook readers and reel them in. These five tips on how to begin a novel will help create the perfect hook for your book.

1. Begin your novel on the day everything changes

You don’t need to share your characters’ family tree with the reader before the story gets going. If your story begins like this:

That November, all she wanted was for Grandma to visit. It had been weeks since she ate one of her grandmother’s apple-cinnamon cookies, which had been passed down from her grandmother’s great-great-great-grandmother, who came over on a boat from Norway looking for a better life. In fact, all of her family loved the cookies. Her Uncle Bert said…

Yawn. Sorry, lady, but no one cares. If you feel the details like those about the cookies are important, find a way to weave them in later — in bits and pieces that are relevant to your story.

Here are other book beginnings to avoid:

- Your character rolls out of bed and starts his day.

- Your character has a super exciting, wild adventure…that turns out to be a dream.

- Starting with a huge description of the setting — unless the setting has a creepy or extra-funny tone to it.

- Opening with a bunch of dialogue. Ground us in the characters’ minds, setting, and actions first!

- Your character is sitting around thinking big thoughts (boring!).

So what should you do instead? Start your story the day your protagonist’s life changes. Hint at this change in the very first lines, as Celeste Ng does in Everything I Never Told You.

Then let your character experience a tiny bit of normalcy with that shadow hanging over her. Let readers fall in love with her before you end your chapter with the inciting incident — the thing that changes everything in your character’s life.

2. Shorter is usually better

If you look at the example hooks above, you’ll notice that most of them are short. The exception is Tommy Orange’s There There, which goes to show you that there are exceptions to this rule.

But in general, readers respond more quickly to something that’s not long and drawn out, like the “It was a dark and stormy night” paragraph.

Of course, in the first draft of your novel, you just need to get the words out. When you come back to revise, edit, and polish, that’s when you’ll hone your hook into something precise and compelling.

Example A — First Draft

There was nothing the girl enjoyed better than sprinting down a dirt road. It made her feel free and light and fast as lightning. On that particular day, though, something jerked her out of her reverie, made her stop short and whirl around and stare: a big sack-like thing lay by the side of the road. The girl made herself step closer, and what stood out to her was a fingernail with a star painted on it.

In this hypothetical novel, the first line is…meh. Yes, a girl is running, but that alone isn’t all that interesting. It gets more intriguing when the girl sees the “sack-like thing,” but it needs work.

How can we take this same scene and rearrange it to make it a concise hook?

Let’s give it a try.

Example B — Second Draft

Before she discovered the body, the girl had loved running. But after, she couldn’t step onto the dirt road without careening back to that horrible morning. The slumped sack in the ditch. The smell. The hand, intact, with a star painted on the thumbnail.

It’s not perfect, but it’s more interesting: the body is mentioned right away, and the girl’s trauma follows. Readers wonder whose body it is and how the aftermath will affect the girl.

And of course, it’s shorter. More precise. Easier for a reader browsing books in the bookstore to process.

3. End each paragraph with something intriguing

Much like it’s a good idea to end your first chapter with the inciting incident, it’s also smart to look through your first chapter and see if each paragraph ends with a sentence that piques reader curiosity.

There’s no point crafting a deliciously compelling first sentence if everything that follows is boring.

Remember, readers have easy and instant access to hundreds and hundreds of TV shows and movies. You have to work hard to make them want to read your book instead — but it can be done!

Don’t be afraid to deconstruct each chapter, scene, and paragraph to make sure everything on the page is interesting.

4. Use sentence structure to drive home a point

Tommy Orange does this beautifully in There There with the repetition in the first line of his novel. Each time he talks about the Indian Head Test Pattern — which was a real thing and which no one seemed to blink twice about — he makes it sound more appalling.

How can you manipulate the language in your first few lines to drive home a point or hone in on a small but deeply important detail?

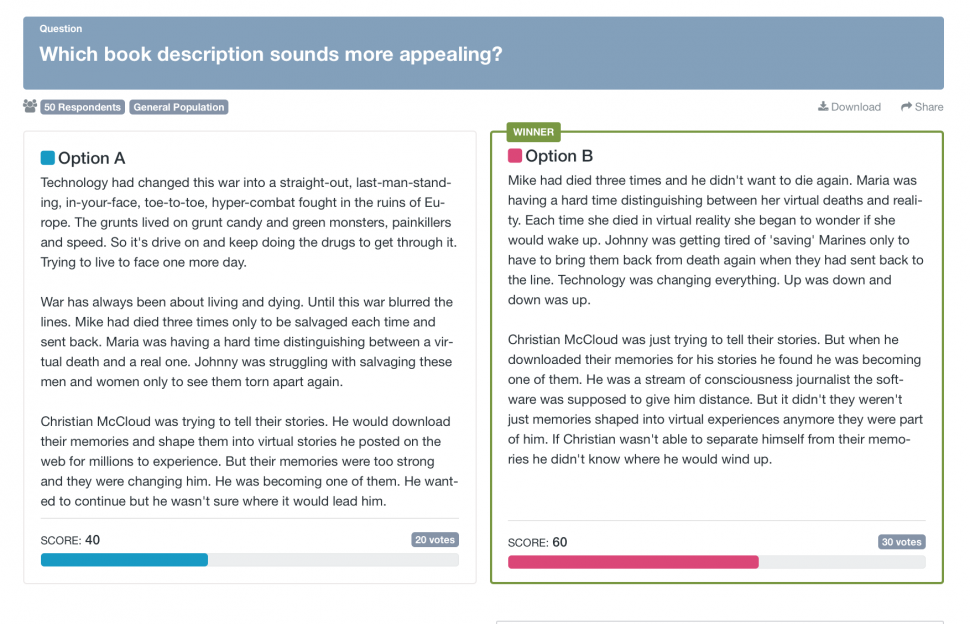

5. Find a critique group to read your novel for you — or run a PickFu poll!

If you’re part of a local writer’s community, take your first pages to the group and see what they think. But here’s a warning: your critique group partners are generally your friends. They love you and don’t want to hurt your feelings too much. They will give you wise insight, but they won’t be unbiased.

Sometimes, unbiased criticism can shine the brightest light on that crucial first page.

Lots of authors use PickFu to test different aspects of their books, including first pages and blurbs. With PickFu, you’ll get unbiased respondents on that first sentence, paragraph, or even page. Split-test a couple different versions of your novel’s opening. See which one your readers (aka poll respondents) like best, and why.

You can even target your audience to include Amazon Prime members or people who read a certain number of books per month.

Once you receive feedback from a poll, take a deep breath and read it all. Take what stands out to you and apply it to your novel — and watch as your first page becomes even sharper than before.

Whether you’re self-publishing on Amazon or submitting to a literary agent, PickFu can help you polish your first pages until they’re so powerful or funny that nobody will be able to stop reading.